- Home

- Samuels, Mark

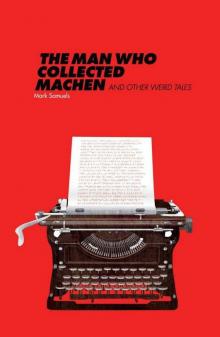

The Man Who Collected Machen and Other Weird Tales Page 2

The Man Who Collected Machen and Other Weird Tales Read online

Page 2

He cupped water from the tap in his hands and splashed it across his forehead, his cheeks and his beard. He looked again in the mirror, and to his relief, saw only his own face and the background of the toilet, but nothing more.

He passed along the corridor to the next carriage and found the buffet cabin situated in a small section at the end. The metal shutter in front of the counter was down, and Knox knocked on it, hoping to draw the attention of a recalcitrant railway staff member. The possibility that the buffet was closed on this service was one he did not wish to entertain; such was the desire he had for the relief only alcohol could provide. There had been no initial response to his knocking and so Knox tried again, more forcefully this time, using his fist, until he felt someone tap him on the shoulder. Knox turned and saw the train conductor. This individual was muffled up against the cold and had wrapped a scarf high above his neck and just beneath his nose. He wore a tatty railway-issue greatcoat, with the collar turned up and it seemed, from its condition, the garment had seen many years of service. His dark green cap was pulled down low across his forehead, its brim resting on the top of thick-lensed and impenetrable eyeglasses.

“Ticket, sir?” the conductor said, his voice hollow and his English heavy with an Eastern European inflexion.

Knox rummaged in the pockets of his jacket, turning over loose scraps of paper, until he remembered he had no ticket and had intended to pay his fare on the train.

“I have no ticket,” Knox said, “can’t I buy one from you now?”

“More money. Two hundred zlotys,” he said.

“I see,” Knox replied, irked that the conductor had immediately marked him out as an American tourist, and was prepared to take financial advantage accordingly. Still, Knox thought, perhaps the man could be useful.

“How much extra would it cost to get a bottle of something warming to drink from the buffet? How about a discount for U.S. dollars?” he asked, pulling out his wallet from the inner recesses of his tweed jacket with the pinkish cuffs.

“Buffet is closed. No buffet. No drink. Unless you pay maybe,” the conductor said, as his head nodded towards the notes Knox had drawn out and held in his hand.

The conductor flashed a set of keys attached to a chain that he drew from the pocket of his greatcoat and rattled them ostentatiously. He unlocked the door of the buffet cabin, disappeared inside and then emerged a few moments later bearing a half litre glass bottle and a plastic cup.

Knox handed over twenty dollars in denominations of five each. He was not at all sure whether this amount would cover both the cost of the ticket and the unknown booze provided by the conductor, but the man looked at the notes, held them up to the lamplight above their heads and grunted something unintelligible Knox took as a sign of satisfaction.

For his part, Knox was busy examining the bottle he’d just purchased. It contained a cloudy green liquid. The label gave no clue, at least in English, as to its contents. It was decorated with an obscure design, something five-pointed and akin to a swastika. Certainly, at least, the legend ‘85% vol’ inspired confidence.

“It’s good,” the conductor said, as if aware an American would not be familiar with the brand. “It is the Nepenthe drink.”

“A brand of absinthe?” Knox asked.

“Better. You drink. Have a good trip.” He laughed and then shuffled off, making his way along the length of the corridor, swaying with the motion of the train.

Knox went in the opposite direction, back towards the coach in which he’d boarded the train. He wanted to lose himself in the strange green liquid as quickly as possible and feel it coursing down his throat, filling his stomach with warmth and turning his brains into a soothing grey mush. He noticed that his fellow passengers appeared to be as uninterested in mingling with one another as was he; they sat as far apart from one another as they could, in individual compartments where possible, or at the opposite ends of seating where a compartment was already occupied. They slumped in their places as if they had already travelled for hours and hours. Some were either already drunk or else in a dull confused state between sleep and waking. One could not easily tell which.

He pulled open the door to the unoccupied compartment at the rear where he’d boarded and sat down on the edge of the seat, gazing at the liquid in the bottle finding its level as the train rattled over points on the track. It had a screw top, for which he was grateful; since his hands still trembled to the extent he was not confident about working a cork free with his jack-knife (say rather, he thought, grimly, murder weapon). As it was, he still fumbled with the plastic cup whilst pouring out a large measure, and almost split its contents. He knocked back the first dose swiftly, coughing as the liquid passed down into his insides. Christ, he thought, what is this stuff? It felt as if someone had kicked him in the head. He leant forward, feeling a wave of nausea, and was momentarily afraid he would vomit. But after the second shot, taken as quickly as the first, all the unpleasant sensations passed and he was overcome with a deadening numbness. He could not feel the ends of his fingers and toes, his anxiety ebbed away, the tide of fear was at last drawing out, and he exhaled what seemed to be an eternal breath. He slumped back into the long seat and nestled the bottle on his lap, watching the green liquid inside tumble like a captured ocean wave.

The darkness outside made it seem, from within, as if the train were stationary. Knox flopped along the length of the seat towards the carriage window and peered out through the glass into the gloom. He saw vague shapes and branches of trees that had not been sufficiently cut back—their sharp ends scraped along the sides and roof of the train.

His eyes refocused and instead of looking through the glass, he now saw his own reflection on the surface of the window. His gaze was filled with hatred. There was a sneer on his lips. Knox was terrified the reflection would reach across the divide and strangle him. He backed away from the sight, afraid of its taking on the appearance of the torn and bloodied revenant he’d seen earlier. He heard a voice in his head, the same voice as before, but this time the words it spoke were different; “you come closer,” it said, “you draw close to me”.

Knox pulled down the blinds on all the windows and poured himself another dose of the potent bad medicine. His head was swimming, and he heard the sound of his teeth chattering in his mouth. The compartment around him blurred, the overhead luggage racks, the electric lamps and the advertisements on the walls faded from view and he passed out.

•

When he awoke it must have been hours later. His watch had stopped, so he had no precise way of telling just how long it had been. But he knew he still travelled by night for it was dark outside; he had lifted the blind a little to see if it were daylight yet. His mouth was dry and his lips were encrusted with the scum of dried saliva.

The half-drunk bottle of booze had wedged itself between the cushions of the long seat. Alongside it was the remains of the plastic cup, crushed by the weight of Knox’s body where he had lain slumped after having passed out. The light from the compartment’s electric lamps hurt his eyes and so he took out his mirror shades from the glasses case he kept in the breast pocket of his tweed jacket, and put them on. The hangover was so bad he felt he would never recover from it. He took a swig from the bottle, but the taste made the bile rise in his throat. He decided to go in search of the train conductor in order to find out how much further it was to Losenef.

As he passed the compartment adjacent to his own he heard a groaning from within and stopped to look inside. A solitary passenger was sprawled across the floor, face down and motionless. The man was dressed in a badly crumpled light grey suit covered with dark brown stains. He had a foul odour about him, of eggs that had turned rotten. Knox considered, for a moment, ignoring him but then the groan came again and this time it was louder and more prolonged than before. The man in the grey suit had, like Knox, been drinking the green spirit. An empty bottle of it lay just outside his reach.

Knox knelt down, pinching his nose a

nd covering his mouth with one hand to guard against the stench and, with the other, he grabbed the shoulder of the man’s jacket and turned his body over.

His face was a grisly ruin. Half of it had been eaten away by the maggots that writhed and burrowed through yellowish flesh. There was nothing at all left of the eyes; only vacant sockets remained. And then the corpse groaned for a third time, a hollow and despairing groan that issued from unimaginable depths of suffering. Something conscious existed within the shell.

Knox backed away, leaving the hideous cadaver face-upright. And still it continued to issue its uncanny cries.

The next compartment along contained a similar horror. The occupant, a woman with long dusty blonde hair, faced the wall with her hands reached out as if clutching at it for support. She made heartrending sobbing and snuffling noises. But she was dead. The skin on her hands was flaking away like paint on a weather beaten wall, and Knox was glad he was spared the sight of her face, for the malformed sound of sobbing could only emanate from a deformed mouth.

The litany of terror was repeated throughout the whole of the carriage and, so too, throughout the next. All the passengers were dead but not one was silent.

Knox took a deep breath and leant with his back to the wall behind him. He took off his mirror shades, rubbed his eyes with his knuckles, and spat on the floor. This was junk, he thought. He’d written stories worse than this in his time. He didn’t believe any of it. He must have bashed his head on something whilst he was sozzled, causing him to hallucinate. He had impacted his skull, affecting the brain, resulting in a wild bout of concussion. The more he thought of it, the more the idea fitted. He was having a psychotic episode. Nothing more. He had killed no-one back in Strasgol; he’d only imagined he had. All this business on the train was brought on by a bump to the head. He put his shades back on and grinned. Then he ran his fingers over the entirety of his skull, working through the mass of red hair that covered it. His grin evaporated. There was no damage to his skull.

The train began to slow down and finally drew to a halt amidst a grinding screech. From further along the corridor, out of the buffet cabin, the conductor emerged. He’d removed the long scarf he had wound around the lower half of his face. Now Knox could see why it had been covered up. There was no lower half of his face. Where there should have been a bottom jaw there was instead a gaping bloody hollow. The conductor’s voice issued from a vacuum, and without tongue or lips should have been impossible to form. Yet the sound was as real as when he had spoken previously.

“Last stop, sir,” the conductor breathed, “Losenef.”

What was odd was that, after disembarking from the train, Knox found Losenef to be an exact duplicate of Strasgol and, moreover, he had arrived an hour earlier than he departed. It was only in the Zacharas Café, having spotted the duplicate of himself drinking Jack Daniels, that he realised the truth. He’d wait a little longer and then try yet again to take his revenge. Eventually, he hoped, he would succeed.

The Man Who Collected Machen

I am writing these lines from a deserted residence situated, I suspect, in the maze of streets to the southeast of King’s Cross, that dim region of London Incognita. I found the house, abandoned for years, when I was lost. It is a squat Georgian villa in the most squalid quarter of the district, its mock-portico decayed, its peeling stucco exterior riddled with weeds. I know now I cannot find my way back from there, and this fact must ultimately put an end to my former existence.

My name is Robert Lundwick. After I had turned twenty-one, in 1969, I came into possession of an income, a legacy from a distant relation whom I scarcely knew. Formerly I had hoped this income would prove sufficient for all my needs. Alas, the gulf between dream and reality! Legal costs had drained the capital of a great deal of its worth. What remained for me was a mere pittance, enough to keep me from starving but not enough to allow for any degree of comfort. I had long ago determined I would devote my life to literary scholarship. Not, let me emphasise, the dry-as-dust scholarship of academe, the crushing orthodoxy to be found in universities, but rather the recondite scholarship that is a journey into the unknown. I refer, chiefly, to those dead authors whose works savour of the uncanny and the marvellous, authors whose unique perspectives are beyond the self-stultifying purview of the modern critical mania for so-called realism. For my part, I chose the mysteries, and the hierophant of mystery was an obscure author called Arthur Machen. Although I had done the best I could to collect a small library of his books, carried with me from lodging to lodging in a battered suitcase as evictions forced me on, I had not sufficient funds for the purchase of the rarer volumes whose cost was beyond my limited means. And so, like many a poor scholar before me, it was necessary I devoted myself to the Reading Room of the British Library.

Dome of a million forlorn hopes! Dome beneath which labour benighted dreamers and unfortunate seekers after knowledge; victims of vanity, slaves of solitude! A legion of bibliophiles weighed down by the learning of centuries. They lift their eyes from their musty tomes but infrequently, gazing with bleary eyes at the enclosed immensity in which they have chosen to incarcerate themselves. Oh monstrous dome! Draining the life from all those scholarly unfortunates who cluster in the radiating rows of desks below. In truth no refuge thou art, no shelter and no haven. Titanic, far-lifted and terrible dome; would that those who come to thee rather fled at once from the silent shades paying thee homage!

It is with an uncanny recollection I now think back to the day I first took my place at my desk and began my study of the work of Arthur Machen. One of the dusty assistants brought me the five items I had selected from the massed ranks of the library catalogue. The items were four in number; the biography by Charlton and Reynolds, the Goldstone and Sweetser bibliography, Precious Balms and The Children of the Pool and Other Stories. These were books I had heard of only by reputation and although I had once seen a copy of the last of these august tomes in the closed, glass-fronted bookcase of a certain bookseller in Bloomsbury, its exorbitant price tag forced its swift return to the shelf. I made copious entries in my notebook, drawing deeply from the biography. I plunged with joy into my researches, was appalled by the notices Machen had reproduced from ignorant critics in Precious Balms, and when I came to the bibliography I realised the extent of his more elusive literary productions, scattered throughout periodicals and American limited editions that had avoided entry in the catalogue of the British Library.

But I came time and again to my desk under the dome during the following weeks, determined to mine the seam of literary gold at my disposal until I had exhausted it. Volumes that had eluded me, such as The Green Round, The Anatomy of Tobacco, The Secret Glory, Dr. Stiggins and The Canning Wonder were pored over in excitement and triumph.

There were disappointments too. Upon consulting the library’s copy of The Cosy Room and Other Stories I found that a vandal had cut out the pages containing a story called “The Lost Club” and, in their place, gummed in a single black page. At the time I did not realise the significance of this deed. I knew of “The Lost Club” only as an obscure Machen tale first published in the journal The Whirlwind in 1890. Although it had been subsequently reprinted in the American edition of The Shining Pyramid published by Covici-McGee in 1923, I found that, here too, the vandal had been at work.

At night, when I dragged myself back to my dingy bedsit in Soho, I would open my battered suitcase library and read again by candlelight those works I was fortunate to possess for myself; amongst which were Holy Terrors, The London Adventure, The Hill of Dreams and The House of Souls.

But when at my desk, beneath the oppressive dome, it was to the bibliography I most frequently turned, and I dreamt of acquiring for myself all those fugitive items listed therein. I had consulted the book on so many occasions that the assistants of the library often brought it to me with an indulgent smile.

During one of my consultations within its pages, a gentleman who often took the desk adjacent to mine, whi

lst pursuing researches of his own, finally addressed me in a low whisper. For weeks we had been on nodding acquaintance, but as time passed I could not shake off the feeling he had begun to take an interest in my choice of research material. For my own part, I scrupulously tried to avoid taking an interest in the spines of the volumes on his desk.

“Please excuse me,” he said in a low voice, “but I cannot help having noticed you have a dedicated interest in the works of Arthur Machen. I have something of an interest in his life and work myself.”

These words arrested my attention and I took the opportunity, for the first time, to properly examine his appearance and not merely glance at him. He was a striking figure, very tall and acutely thin, and dressed in an olive-coloured corduroy suit. He wore a crimson and paisley cravat rather than a necktie around his throat. With his natty little moustache he looked like an out of work actor. But for all his sartorial flamboyance, it was obvious that he was a very ill man. His skin was almost the colour of cigarette ash.

His smile was warm enough, but there was something about his eyes that was dead and emotionless. He stared for longer than was normal, as if he were involved in some game of wills, whereby he would not be the first to blink or drop his gaze.

“My name is Aloysius Condor,” he said.

It had occurred to me that the man might be a homosexual. Since the recent legalisation of the practice by parliament, such individuals had appeared to multiply in the “let-it-all-hang-out” permissive era of Carnaby Street, the Beatles and what some had lately taken to calling the “Swinging Sixties”. Being of a liberal cast of mind, I tried not to react to the possibility by displaying any sense of unease in his presence, my duty, after all, being to respond in the manner of one polite scholar addressing another in the spirit of a commonality of interests.

The Man Who Collected Machen and Other Weird Tales

The Man Who Collected Machen and Other Weird Tales